“I have found out there ain’t no surer way to find out if you like people or hate them than to travel with them” Mark Twain.

Many of you will be familiar with the adventures of Ed March, the man who gained quite a level of notoriety for riding the most common motorcycle in the world. If not, I recommend you check out his YouTube Channel C90 Adventures where he rides his humble C90 Honda to far flung corners of the globe. But what is it that makes a man like this tick? What is his motivation? Why? I decided to investigate a little deeper if I could.

First I had to track him down, and as is Ed’s want, I find myself in Mongolia at the Oasis Guest House in Ulaanbaatar in company with an eclectic mix of likeminded souls all itching for adventure. We will spend the next 16 days roaming the vast Mongolian Steppe by motorcycle and I will hopefully reach some sort of understanding of Ed’s psyche and perhaps some of that sense of the absurd might rub off on me.

First order of business was to hire some bikes. BMW’s? KTM’s? Maybe even the venerable Royal Enfield? No, the only real option in Mongolia is the mighty Shineray Mustang. 150cc of Chinese misery on 2 wheels redolent of an early 1980’s Japanese farm bike with luggage racks and crash guards everywhere. They are magnificent! And at a cost of thirteen Euros per day very affordable.

Our journey commences with an ominous warning as after just 14 meters (yes that’s not a typo) we suffer our first breakdown when Christina’s bike starts spewing fuel out of the carburettor. It was a simple enough fix and we make it another few kilometres before several other adjustments need to be made to various bikes just to get out of the city. Once out of the city however the magnificence and visual splendour that is Mongolia begins to reveal itself. The annoying failures of our bikes become slightly less bothersome, and the magic of the landscape begins to cast its spell on us.

The hardest thing for a westerner to get their head around in Mongolia is the total absence of the concept of private ownership of real estate. Anywhere and everywhere (except for a couple of National Parks) is open for you to explore. Nothing is off limits. There are no fences, no signs and virtually no boundaries. You want to ride your bike up that mountain? Off you go! You need to cross the river? Find a shallow spot and plunge on in! You don’t like the “road” that you are on? That’s OK just make a new one. I put “road” in inverted commas because these are not roads as most of us would recognise them but usually just a series of wheel tracks across the wilderness.

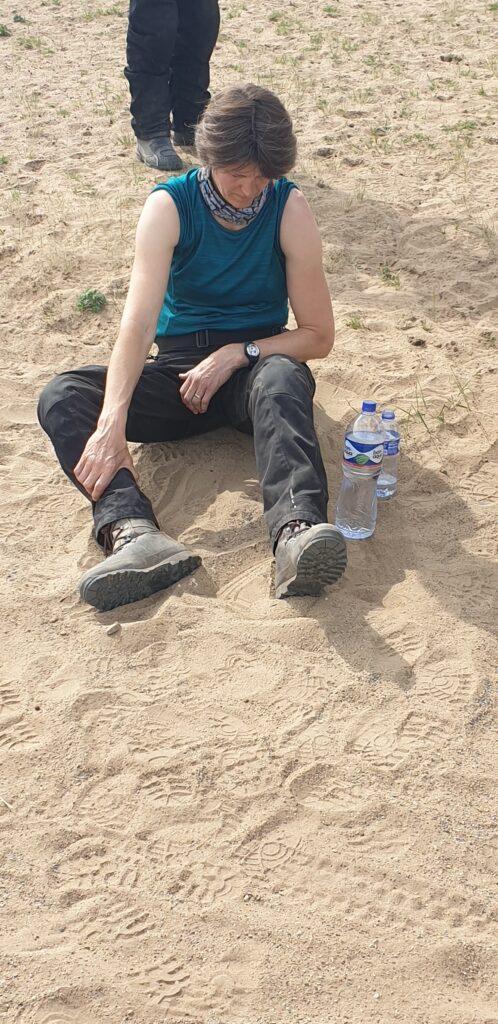

Over the next two weeks we would ride our hateful little bikes up those mountains, across those mighty rivers and make our own roads through the wilderness. On day three Christina crashes heavily on loose sand injuring her shoulder. At first, we think it is dislocated and ponder what to do when Ben discovers he has 4G coverage if he stands 50 metres away on a sand hill, so he googles “dislocated shoulder treatment” and we proceed to administer first aid while Ben shouts instructions from afar. We give her what pain relief we can, load all her luggage on husband Steve’s bike and she bravely rides 40km to the next town where there is a “hospital” which turns out to be a crumbling Soviet era block of despair with a hessian front door. We send a local street urchin to fetch the doctor who is on her lunch break. She is ultimately unable to do any more than we already have done and recommends we go to the next larger town where there are at least Xray facilities. So Christina, by now in a mildly narcotic stupor, saddles up again for the ride across another 50 km of impossible terrain. Eventually she is pronounced well at the next “hospital” but unable to continue. She and Steve volunteer to make their own way back to Ulaanbataar.

We continue, our merry band now somewhat subdued and more respectful of the risk. Our group now numbers just five and we soon shift the weight of our concern for Christina toward the rear of our conscience as Mongolia continues to bewitch us. Most nights we camp within sight of a nomadic family in their Gher, the ubiquitous round tent dwelling most of you will know as a yurt, but that is the Russian word and Mongolia broke those ties in the 90s. We watch in awe as horsemen move large mobs of yaks, goats, cattle, horses, sheep and even camels across the vast rolling, empty landscape. We camp atop mighty mountains or beside crystal clear streams.

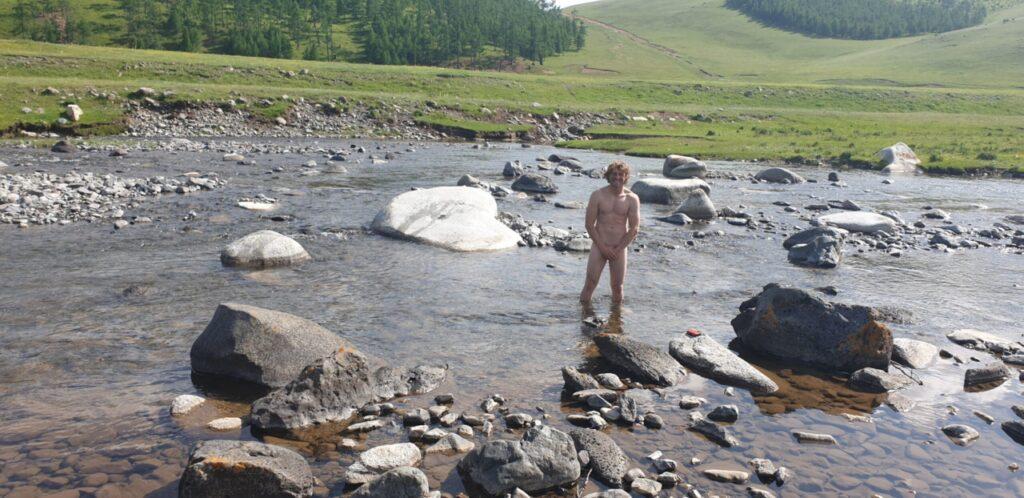

There is a cultural imperative in Mongolia that you do not bathe in the streams but if nobody sees us, did it really happen.

Five naked western men just regain their clothes in time as a lone horseman pauses briefly to attempt to converse. Neither of us speak the other’s tongue but with much sign language and the almost universal currency of vodka we somehow learn that he is the protector and defender of his family and thus he welcomes us to his beautiful valley.

Once or twice we treat ourselves to the trappings of modern life usually confined to the tourist on the organised itinerary complete with guides and porters. But what is considered five-star luxury in Mongolia would be laughed out of business in the west.

We luxuriate in hot springs and we scale mighty sand dunes

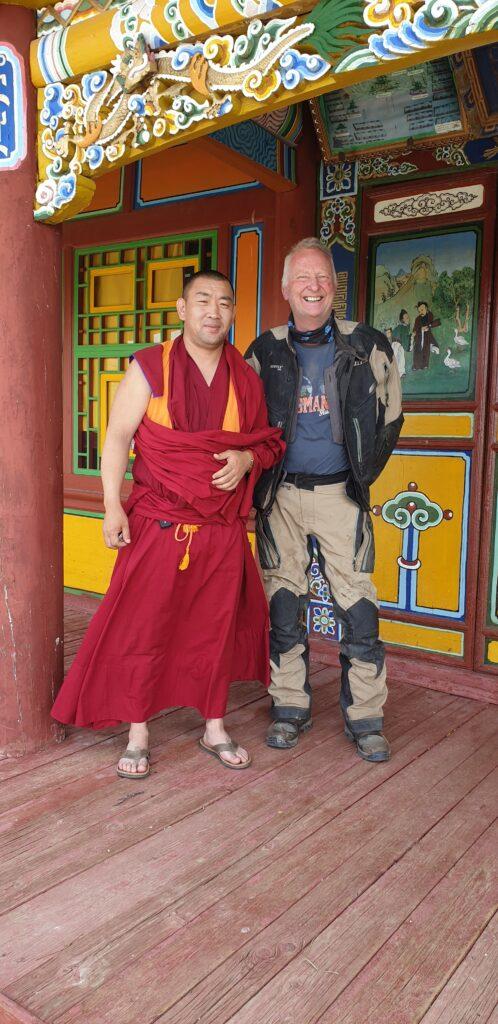

visit an ancient monastery and meet the resident monk who has lived here for twenty years.

We mend countless punctures and ride at maniacal speeds across the desert, we suffer crippling food poisoning and share the fabulous hospitality of a local family who ask nothing in return and all the while we hope the rush will never end.

But end it must and too soon we are back in Ulaanbaatar where we find Christina and Steve in high spirits despite their arduous return to the capital. I had set out to discover a little of what it is that makes some people tick. Did I learn the secrets of the adventurer’s mind? Maybe, but in the end, I realised that I had learned a whole lot about myself and my place in the world. I already am an adventurer and perhaps we all are to a greater or lesser degree. Mongolia has a magical quality about it that leads one to do some intense naval gazing and I discovered, as the French novelist Gustave Flaubert once observed “Travel makes one modest. You see what a tiny place you occupy in the world”. If ever there was a place to compel you to reach this conclusion it must be Mongolia.

More pics